My wife Kelsey is given a straightforward request before we trek Mount Storm King: don’t geotag your pictures.

A coworker who reached the summit with a number of hiking influencers posted pictures on Instagram and informed Kelsey about the trek. We are cautioned not to enrage the hiking influencers as it is best practice for them to share their images or videos with only the term “Washington state” in the location.

We are informed that the concept is environmentally driven. “Viral hikes” can clog up trails and cause trouble in tiny towns. For instance, the Washington Trail Association recently completed a significant repair of the photogenic Rattlesnake Ledge route in North Bend, just outside Seattle, which now attracts more than the annual visits anticipated when the trail was first built nearly 20 years ago.

The bulk of Washington’s hiking trails are congested around Seattle due to heavy foot traffic, which occasionally causes inadequate parking, overflowing trash bins, and difficult summit and overlook navigation.

The “no tagging” rule annoys me immediately, despite its potential good intentions. Kelsey and I have gone hiking almost every weekend since we moved to Tacoma last summer. We have completed the majority of the well-traveled trails in the Seattle area and have begun traveling further to less populated regions for diversity.

When my wife and I visit more popular routes, we get out early to avoid the throng and typically have plenty of room to ourselves as we ascend. It’s a different scenario on the way down, but I don’t mind the increase in traffic as we drive downhill. It’s lovely to see so many people enjoying the outdoors, but a selfish part of me still yearns for solitude and privacy, that privileged fantasy of being by myself in the vast unknown.

Organizations like Leave No Trace, which once promoted the idea of “tagging carefully” in 2018, appear to have outmoded and poorly understood social media policies that are the root of the geotagging ban.

The new Leave No Trace rules, which were updated in September 2020, assert that they are not anti-geotagging and forbid bullying or public shame of people just discovering nature. Nonetheless, I suppose it’s challenging to maintain exclusivity if a location becomes not only widely accessible but also well-traveled. My initial thoughts turn to entitlement, riches, and sponsorship money once Kelsey is asked not to tag our trip.

Who gets to select who nature is for if it’s not meant to be for everyone?

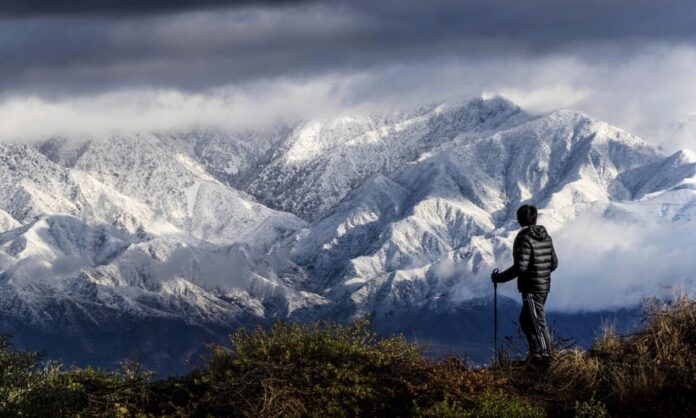

the San Gabriel Mountains, which are located in southern California to the east of Los Angeles, as seen from the Hidden Hills trail in Chino Hills. image courtesy of AP’s Watchara Phomicinda

Mount Storm King is a trail that is conveniently located in a national park on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington, but getting there requires some planning and driving expertise. It takes over two hours to get there from our Tacoma rental house, largely on backroads and state routes. Gas stops, tiny cafes, and neon-lit casinos are everywhere along the way. We reserve an Airbnb in nearby Sequim for Friday and Saturday so that Lucy, our dog, won’t be left alone at home for too long.

Kelsey and I plan to arrive at the trailhead early as usual. At a largely empty parking lot close to a ranger station, our vehicle is one of a small number there. Given the earlier warning we received, I am taken aback by how peaceful it is despite a few other hikers strolling around.

Jaime Loucky, the chief impact officer for the Washington Trail Association, tells me over Zoom a few weeks before our trip that “making the outdoors a place for everyone” is a cornerstone of the work the WTA performs. Since it is a public area, it must be friendly and inclusive.

He believes that a good spin may be put on the influencer economy. You might consider it a challenge, but you might also consider it an opportunity. We’ve discovered that there are many different channels through which people might learn where and how to go outside.

The WTA takes pleasure in being among the best resources for finding that information. Loucky claims that the WTA is well aware of how well-liked and Instagrammable some trails are, but that’s not the issue. Although the population in the area has been increasing for a while, there hasn’t been a parallel increase in access to the outdoors.

The WTA provides comprehensive information on trail conditions without a paywall in the belief that by enabling more people to enjoy nature, volunteers, legislators, and businesses will increase their contributions. Instead than reducing the number of hikers, sustainable hiking calls for systemic change that is centered on equality, environmental protection, and stewardship education. They put a lot of effort into conserving and maintaining the trails, educating more people about the delights of hiking, hiring young people who enjoy the outdoors, and emphasizing sustainability.

According to Loucky, the increase in trail users since the epidemic started has given the WTA the opportunity to push for increased state and federal support. According to the group, fair and sustainable hiking will call for more environmentally friendly infrastructure, more trails, improved access to reasonably priced equipment, and teaching a younger generation of hikers. We can establish fresh strategies for preserving trails, combating climate change, and fostering economic growth. One of the ways we can build a more sustainable trail network and strengthen Washington State’s ability to adapt to climate change is by connecting those three.

In order to reach the summit of Mount Storm King, we must travel across a number of continuous ropes that are fastened to tree roots and trunks and span-sloping areas of scree. I put on some winter gloves to shield my hands. We watch for a man to fall from the first rope. No one else is at the top, he tells us when he gets to us, but it is chilly and windy. As we get there, the vista is breathtaking. Our peripheral vision, which overlooks the deep blue lake, is divided in half by lush mountain peaks and the other half by the Puget Sound and Canada.

I just have to: I take my iPhone out of my coat pocket and take a few pictures and a little video. When I finally get to Kelsey, we take a number of selfies together, the cold, uncompromising gusts of wind making our faces flush.

We run into large crowds climbing the mountain as we make the arduous descent. Is there sufficient service up there to post to Instagram, one of the young couples quips as we move aside for them. It’s already about 10:30 a.m., late enough in the day for the route to be busy. The trail protocol for passing one another while traveling in separate directions seems to change every time. Other times, as we move out of the way, others wave to us as well. The parking area is crowded when we go back to the ranger station. Groups consume sandwiches and beer from open trunk-mounted coolers. After speaking with Loucky, I idly consider how this location could be able to support more people, proper public transportation, and recycling and composting.

Kelsey and I take our dog to the patio of a pub in downtown Sequim later in the day when the sun has warmed the ground. In the distance, snow-covered mountains rise into the sky. A few of the older residents in the area start a conversation with us over a beer and inquire about our morning hike. They instantly suggest Pyramid Peak after hearing about Mount Storm King, saying that the view from the opposite side of Lake Crescent is better.

Kelsey has already noted half a dozen new hikes that are not on our list by the time they are getting ready to go. Because thus far, our experience in Washington has taught us that there is always a better walk, a higher mountain, or a finer vista somewhere else, I can’t help but giggle. We thank the pair for their recommendations and bid them farewell.

There is too much terrain to cover in under ten years for the average weekend hiker. I find it impossible to conceive of doing it alone.